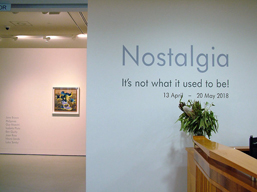

Nostalgia: it's not what it used to be

13 April – 20 May 2018

A contemporary take on nostalgia - both critical and humorous.

Jane Brown Phil James Guy Maestri Izabela Pluta Ben Quilty Joan Ross Niomi Sands Luke Temby

nostalgia (noun)

1. a wistful desire to return in thought or in fact to a former time in one's life, to one's home or homeland, or to one's family and friends; a sentimental yearning for the happiness of a former place or time.

2. something that elicits or displays nostalgia.

nostalgic (adjective)

1. experiencing or exhibiting nostalgia, a sentimental or wistful yearning for the happiness felt in a former place, time, or situation.

conceit (noun)

1. an ingenious or fanciful comparison or metaphor

Wistful desires and sentimental yearnings, the things of which nostalgia is supposedly made, perhaps once, but no longer. Whilst we may look back and search for meaning and understanding in the past, art often does so with a critical and unsettling eye; to make sense of our present, to articulate an intention or desire for what lies ahead.

Each of the artists in the exhibition utilise nostalgia; some visually or conceptually more obvious than others to question, to unsettle, and to provoke.

Jane Brown

Sporting Country comprises a suite of photographs of places related to sport in rural Australia. Brown’s small and thoughtful black and white portraits of sporting clubs, stadiums, swimming pools and monuments contrast with the colour, energy and fervour of Australian sporting life.

Central to the series is the notion of ‘faded glory,’ which evokes both nostalgia for a bygone era and the ongoing and passionate support of local sporting activities. The meticulously tended bowling greens and football ovals pictured in these photographs testify to the determination of small town communities to maintain humble but much-loved sporting facilities in the face of a shift in support from local clubs to national and international teams.

Photographed with film and hand-printed by the artist, these carefully constructed images speak of forgotten ‘legends’ and declining regional populations. There is a beauty and melancholy in this stasis that reflects Brown’s long held interest in the temporal. With great attention to detail and an anthropological eye, Brown captures the layers of history and the complexities of culture within the spaces she depicts.

Sporting Country debuted in the prestigious Basil Sellers Art Prize, which commissions contemporary Australian artists to contribute to ‘the critical reflection on all forms of sport and sporting culture in Australia’

Philjames

Philjames doesn’t want to make art; he wants to re-make it. Under his careful hand, famous (and not so famous) paintings are given new life, as he takes iconic masterpieces and inserts a splash of pop culture into them.

But it would be a mistake to see Philjames’ art simply as fresh-faced vandalism, because it is as much about restoration as destruction. Scouring the shelves of thrift shops, his process begins with a search for once loved art-prints that have long since lost their sheen,. ‘These works would have been on somebody’s wall at some point… and then through one act or another they have ended up in this sort of scrap heap.’ he explains. Critically, what (the artist’s) interventions ensure is that these pieces find their way back onto someone’s wall. That is although the process of painting and doctoring of these prints inevitably destroys, it also reinvigorates.

Philjames’ additions all help to transform the experience of the viewer. He takes an austere portrait, adds a twist of humour and transforms the work into a site of play rather than cerebral reflection.

While this intuitive, playful approach lends a refreshing immediacy to Philjames’ work it is not without danger. For the most part, however (the artist) has been able to escape cultural politics by situating the work within the context of speculative history and sci-fi. In fact, he observes that his most provocative religious scenes are often purchased by Catholics. They see the humour in his uncanny renderings.

(extract from Modern Masters, Philjames, Taji Mitsuji, Vault Magazine, October, 2017)

Guy Maestri

The importance of the Hawkesbury River for Macquarie is shown in Maestri’s painting, which depicts the river at night – with ghostly miniatures of Lachlan and Elizabeth in the centre two (of six) panels. Maestri makes a strong statement of place and history, in a subtle and evocative manner. Without the river, the settlement on the rich alluvial soil of the Hawkesbury would have been too treacherous and time-consuming to get from Sydney Cove to the ‘green hills’ of Windsor.

The sombre nature of the painting alludes to the difficulty of managing a fledgling colony in a ‘new’ continent, and the darkness that was an inherent part of this process.

Maestri’s work has yet another layer of sensitivity as he makes a comment about Macquarie’s family life. Each of the six panels can be seen to represent one of the six miscarriages that Elizabeth endured before successfully giving birth to Lachlan Jr, thus further illustrating the connection Macquarie had to the Hawkesbury.

Izabela Pluta

Izabela Pluta’s work offers a spatial and temporal narrative across a set of material investigations generated through a process of ‘gleaning’ landscapes and forms which explore traces, inscriptions and erosions pertaining to measuring time via the medium of photography. As a way of thinking about our experience as it is bound to memory and conflated by the passing of time and the span of geographic separation, her images are intended to appear to be of a certain place, pertaining to something specific and significant - yet the entire premise of their production is to remind us that the very thing we seek to locate and recall is always out of reach.

While the reoccurring element of each work is located within the practice of expanded photography, the method by which the work comes together draws largely on finding, fragmenting, translating and reconfiguring material - that is both photographed and found. Her various approaches are not only bound to photographic reflexivity but engage with the explicit ways that material objects are encountered, experienced, collected, deciphered, presented or interpreted. The components that comprise Threshold (2018) include an image the artist took of a window in her family home when she first returned to Warsaw in 2002; a layered set of reflections inside a natural history museum diorama (originally shown in the series Agency of inanimate objects, Museum (2014); and a blown up fragment of an old postcard depicting tourists gazing into a distant mountain vista.

Ben Quilty

‘My work explores the life that I have led and the subcultures and rituals that best describe the nature of male angst and rebellion. I always think the work I make is fairly autobiographical. I’m not trying hard to build some conceptual framework and, in fact, the more closely I look at my own life the easier it is to make work.’

Quilty grew up in the north-western suburbs of Sydney. He recalls his childhood in Kenthurst as being close to idyllic but this changed in his teen years. Life became looser, more social, wilder, riskier, and cooler. The invincibility of male youth with its bravado, anti-authoritarianism, restlessness, spontaneity and hedonism fuelled a passion for mates, alcohol, drugs, heavy music and risk-taking behaviour. He absorbed it, observed it and used his art to probe its logic. It stimulated a life-long fascination with masculinity – what it takes to be a man, how to define it and how boys become men.

The muscle cars of the 1970s, cult icons to many young males, were also part of this subculture. The Torana and the Falcon were cars that reeked of rebellion. Even their design appeared to push forward in an aggressive way, a way that mirrors the way you would like to be perceived later on.’(4) Quilty’s images of these metal gods, such as Torana #8, personify an idea of masculinity that is strong, powerful, swift and threatening, but not, as it turns out, without vulnerability.

(extract; Kate Caddey, Education Resource Kit, A Case Study, Ben Quilty. Lake Macquarie City Art Gallery, 2015)

Joan Ross

In Australian slang, BBQ this Sunday, BYO means Barbeque - Bring Your Own Alcohol. It is an invitation, in this case to re-enact the process of colonisation through the modern cultural ritual of an Australian summer picnic. Joan Ross invites us to gather in an Australian landscape painted by convict Joseph Lycett, an Englishman transported for the crime of forgery. Ross forges the forger, rearranging his 1800’s view to accommodate a contemporary history story.

On what was once Lycett’s shore, the BBQ has already begun. Freshly caught fish roast on a campfire tended by a group of Aboriginal people. Above them, the untouched southern night-sky flags their ownership of the meeting place beneath it, as they wait for guests with dubious manners. The colonials arrive late, flying in on a tartan carpet, bringing a barrel of rum and a bright yellow high visibility (hi-viz) designer handbag.

Modern hi-vis colours of emergency grow in the ancient landscape as more guests appear, bringing their own artefacts of civilisation. As the crowd around the BBQ grows, the fluorescence that at first seemed out of place becomes almost natural.

In BBQ this Sunday BYO, hi-viz yellow no longer signals an emergency, it signals the commonplace and the ordinary. Ross associates the acceptance of the colours of catastrophe into our modern lives with disastrous civilisation.

(Dr. Lisa Armytage)

Niomi Sands

Artist Niomi Sands explores the often overlooked collections of lost property. Over the past two years the artist has been trawling through lost property collections uncovering somewhat quirky gems that represent our everyday lives. Sands meticulously recreates these collections in thread, the hand-sewn line becoming a ghostly outline and the cross stitched motif transforms in to an abstract study of the lost objects.

Sands’ is fascinated with the collections of objects and material culture that we surround ourselves with and how these objects provide an insight into our lives, aspirations, memories, frustrations and relationships. These objects can signify a lifetime of experiences and often take pride of place within the domestic environment.

The use of thread and the technique of sewing is an ever present part of our everyday lives, it holds together the fabric that we clothe ourselves in, it almost everywhere, sewing can be recreational, domestic and traditionally a feminine pursuit. In the artists’ work, sewing is utilised for its aesthetic properties as well as it cultural ties.

In the work Lost and longingSandsasked the question ‘Have you ever lost something?’ of many friends and colleagues and their subsequent answers are the inspiration for this work. The question sparked lively conversations that centred on memories of these often mundane objects. From the descriptions of their cherished and not so cherished objects uncovered through these conversations, images were sourced digitally. The outline of each object was then cut out of a disposable lens wipe and edged with blanket stitch. Each object celebrates the stories and memories represented by these often forgotten lost objects.

Luke Temby

Luke Temby’s portraits of Lachlan and Elizabeth Macquarie are unashamedly contemporary in nature. Not only has he not concerned himself with historical accuracy, neither has he felt the need for reverence towards the governor. In his soft sculpture, the Macquarie’s become Big Mac and fries, as both Lachlan and Elizabeth are depicted holding onto their containers of fries (not even hot chips!).

The portraits demonstrate that connections can be made across history and culture and remain relevant. It also personalises the man, who had a difficult and complex task in creating a nation out of a colony. Essentially, these small figures display a humour and a quick wit that rounds out the more formal ways in which Macquarie is most often depicted – in a sense creating a connection between the wry, Scots smile he has in his early portraits and bringing that sense to the present day.

Page ID: 108968